Fisherwomen

Following the historic route of the old herring fleet from Shetland to Great Yarmouth, Fisherwomen weaves a compelling tale of a unique phenomenon in the history of British women at work.

The series is presented in three parts: Portraits, Heritage and Journey.

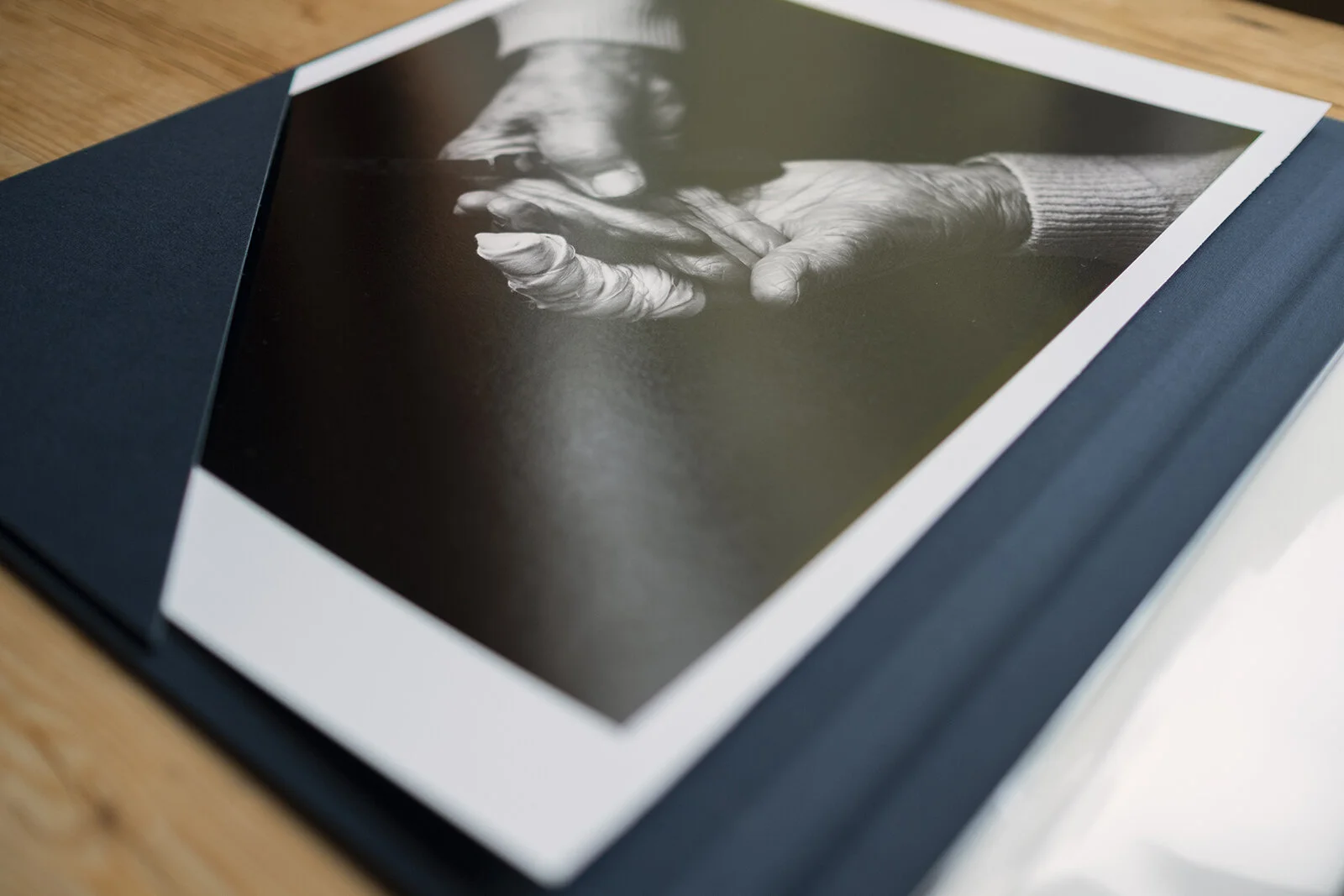

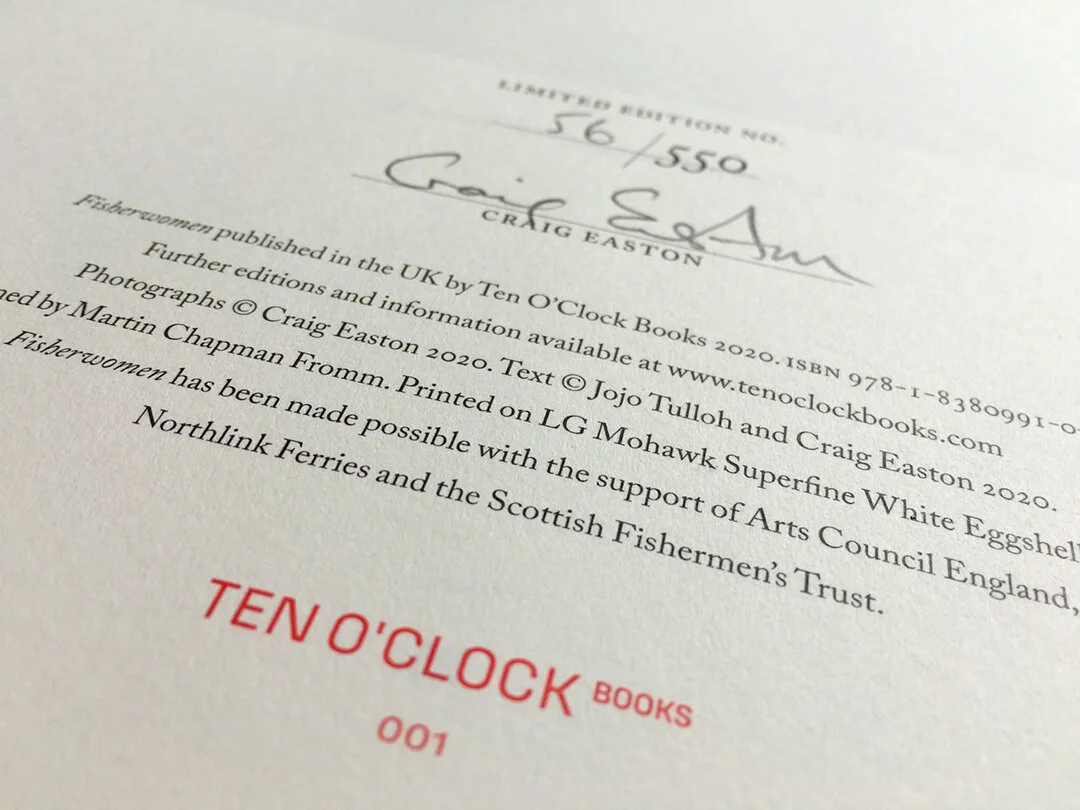

FISHERWOMEN - 24pp large format 15”x11” portfolio available from Ten O’Clock Books

Publication & Exhibitions

Media

FISHERWOMEN

Women have always played a critical role in the fishing industry. From the very early days they mended nets, gutted fish and baited lines, but they also did all the domestic work and raised the children. They even carried their men out to the fishing boats on their backs to ensure that they could go to sea in dry clothing.

Celebrated in the original calotype photographs of Hill & Adamson in Newhaven in the early 1840s and in the paintings of Winslow Homer, Isa & Robert Jobling, John McGhie and others from the 1880s to the 1920s, the east coast fisherwomen were a common sight as they gutted and packed the herring into barrels on the bustling quaysides or carried the catch in baskets to sell door to door. Such characters, in their traditional aprons and headscarves, played no small part in the growth of an artists’ colony that sprung up around the fishing village of Cullercoats – near Newcastle – where Homer briefly settled in 1881-82. This period and the paintings he made of the ‘working bees, the stout hardy creatures’ on Cullercoats beach (page 21) proved to be a turning point in his career marking a new, more confident approach to his painting that, on his return to New York, led one critic to exclaim ‘he is a very different Homer from the one we knew in days gone by’, now his pictures ‘touch a far higher plane…They are works of high art.’

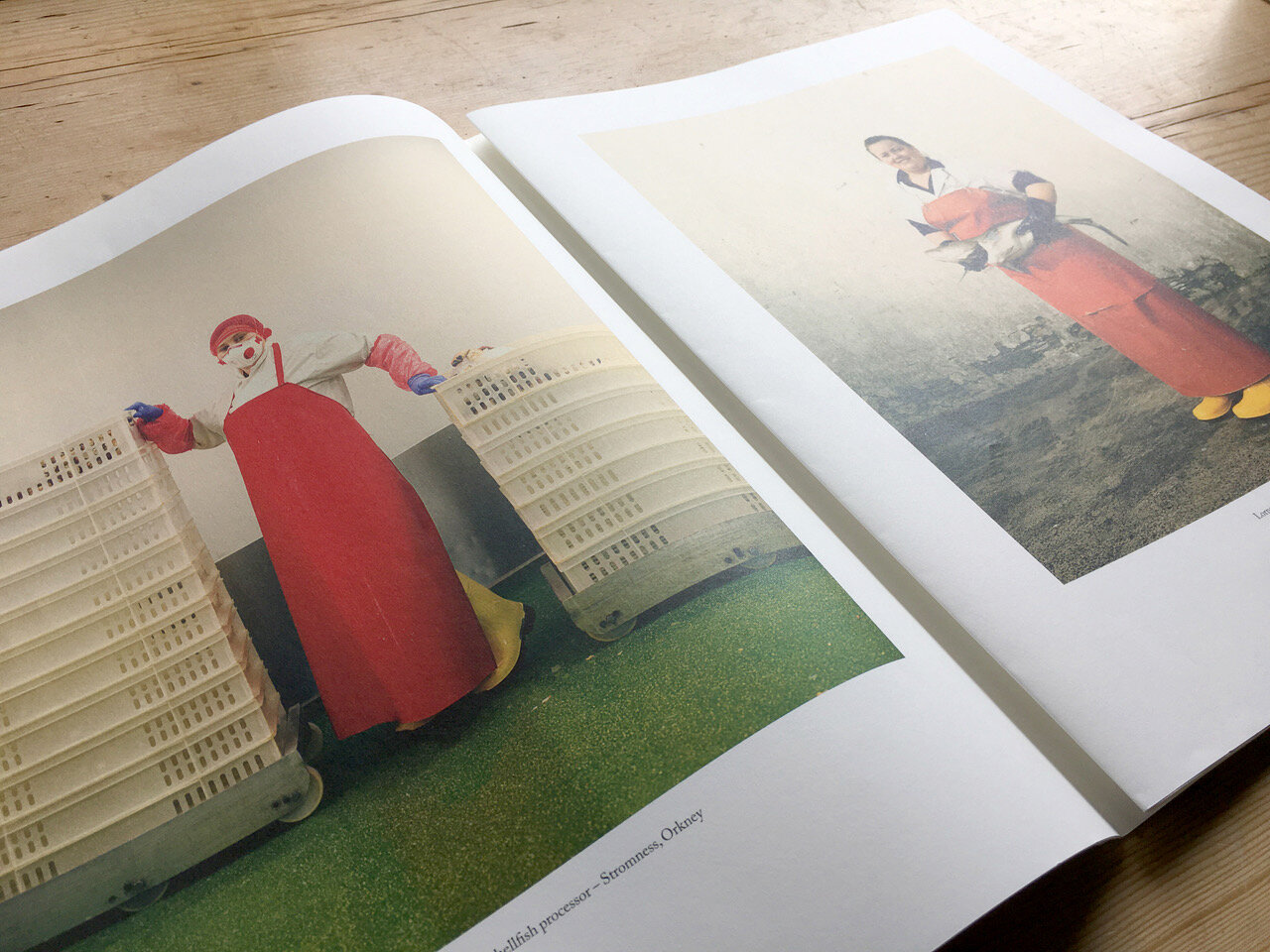

Today fisherwomen are no longer calling their wares on the quayside but are to be found mostly behind closed doors, working unseen in large fish processing factories, smokehouses and small family firms all around the coast.

They are still fiercely proud of what they do. ‘I’ve never had a job like it,’ says Louise Hutchins, ‘it’s constant banter. It’s piecework and I was one of the fastest gutters – it took me a couple of months to learn it and a year to pick up speed. My hand used to cramp up and I used to stab my finger all the time.’

Heritage

The herring lassies are a unique phenomenon in the history of British women at work.

A band of female-only migratory workers, who from 1860 onward left their families behind to follow the Scottish herring fleets to gut and salt-pickle the catch. The work was tough, the salt ate into their fingers and they laboured long hours outdoors in uncovered, unpaved yards surrounded by fish guts, but as workers they were fiercely respected, and the women valued their independence.

The tradition of ‘going to the herring’ was passed from mother to daughter for almost a hundred years and at its peak in 1913 as many as 6,000 herring girls would come to Shetland in early summer, staying in purpose built gutters’ huts and working three to a crew: two gutters and one packer. Both Baltasound in Unst and Wick in Caithness were colloquially known as Herringopolis.

The money was one thing, the camaraderie and freedom from parental control another with many older women remembering the time spent living in cheap lodgings and working long hours gutting and packing on the quayside as a ‘holiday’ despite the physical discomfort of bending down low over the farlan (the wooden trough the herring were tipped into) and the hazards of deep cuts from razor sharp knives.

‘It was awful big fishing one year… It was piled up for us to cut and we never saw the bottom of the farlan for three weeks. They kept on piling them up and up and up every day, but we made up for it when we went to the Palais at night. We had good times. Every Saturday night. Dancing.’

‘At the end of the season, I set off from Lowestoft to London and I was there nearly three weeks. Oh dear, I fairly enjoyed that. I spent all my money. We’d had such a busy season, we were awfully well paid.’

‘I was at Simbister, one year, Lerwick two and then three and then four. And then I married. Silly me. I was twenty-two.’

Mary Williamson

Journey

From the early part of the nineteenth century right up to the middle of the twentieth century, the herring fishery was one of the most important industries in Scotland.

Each year as the shoals swam south through the North Sea, the fishermen of the herring fleet followed them. The east coast men began their journey in Shetland in the early summer and for the next six months sailed south bringing their catch into the fishing towns and villages down the length of the North Sea coast of the British Isles. The annual pilgrimage ended in the early winter at the English seaside resorts of Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft.

Whilst the fishermen travelled by sea, the fisherwomen mirrored their journey by land travelling from port to port gutting and packing the herring into barrels on the quaysides.

The majority were Scots, but they were joined by women from the east coast of Ireland and a few from England, with special trains laid on to take the women south. Before the days of large factory ships with facilities to process the catch at sea, the connection between the fishing ports was tangible: Shetlanders knew Yarmouth, Hull folk knew Fraserburgh and Wick. Even now in Whalsay you’ll hear talk of winters in Lowes-toft, and in Yarmouth tales of the ‘Scotch girls’ annual visits: the cultural connection was real.

‘All the boats used to moor up, tie up at the weekend because the Scots fishermen, they never fished on a Sunday. The Englishmen did, but never the Scots. They all went to church with a Bible under their arm and sang hymns. They got drunk on Saturday, then went to church on Sunday to have their sins forgiven and then Monday they were all out at sea again.’

Edna Donaldson.

FISHERWOMEN - 24pp large format 15”x11” portfolio available from Ten O’Clock Books